"I saw a couple of pictures of ladies who looked a bit like Mother, and might have been me or Jane. But I didn't see any grown-up men who looked a bit like you boys – I wonder why not."A fine example of the genre I like to call 'literary fan fiction': this is a sequel of sorts to E. Nesbit's Five Children and It, in which the eponymous 'five children' (Cyril, Anthea, Robert, Jane, and their baby brother, known as the Lamb) encounter a Psammead, a grumpy being that claims to be a sand fairy, and grants wishes which seldom turn out as the children intend.

Far away in 1930, in his empty room, the old professor was crying. [loc 123]

Nesbit's novel was published in 1902: these children will grow up and come of age just in time for the First World War. Kate Saunders' novel deals with that, and with the Psammead's own past. Five Children on the Western Front opens with a Prologue set in 1905 -- within the timeframe of the original novel -- in which the children ask for another trip to the future, and the Psammead takes them to 1930. (That's where the quote above comes from.) It's a nice way of foreshadowing the events of the main part of the novel, which begins in October 1914 with Hilary (formerly known as the Lamb) and Edie (who wasn't even born when her older siblings met the Psammead) stumbling across the 'sacred sleeping place' of an ancient, irritable desert creature.

The Psammead is especially irritable, it transpires, because it's been through 'some sort of violent magical upheaval' and has been transplanted from its 'proper hole' by powers unknown. ('You're a refugee,', says Anthea.) The nature of that upheaval, and the solution to it, occupies Edie, the Lamb and Jane for the rest of the book. Cyril is in the army, Robert's at university, Anthea at art school, but their stories are as much a part of the plot as the immediate interactions of the younger children with their new friend, the retired desert god.

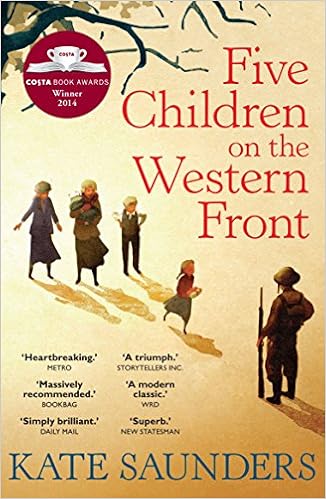

Saunders won the Costa Children's Book of the Year for this novel, though I do wonder how well Modern Children will get along with it: the style is evocative of Nesbit's (though the story's somewhat faster-paced) and the characters very much of their time. There are weighty themes (moral relativity, war, women's suffrage, class inequality) running through the story, though they don't overwhelm the charming, and often funny, fantasy elements.

I couldn't help mentally comparing Five Children on the Western Front to A. S. Byatt's The Children's Book, although the two novels are doing very different things: Saunders is exploring the characters and their futures (and in the Psammead's case, its past), while Byatt is more concerned with the author behind the story. Yet both are concerned with the way that the First World War was a crashing full stop to a myth of an idyllic golden age of childhood. ... And now I want to read the Byatt again!

No comments:

Post a Comment