Let the Switzers be ruled by landsmen, let nations with no sea borders keep their old ways if they wished, but there were navies to maintain, and the deepsmen of the sea were no longer neutral, no longer sailors' yarns, but an engaged force with loyalties of their own. [p. 43]Europe reimagined, with merfolk -- 'deepsmen' -- in alliance with the nations of dry land. It's set, I think, in Tudor times, several centuries after the first deepsman-landsman hybrid, Angelica, walked up out of the water on the Venetian coast and proposed a mutually-beneficial arrangement. Since then, deepsmen have interbred with the royal families of Europe (though the penalties for unauthorised miscegenation are grim and bloody) and any country with a coast has a ruler with some deepsman blood.

And just as in our history, this has led to problematic inbreeding: imbecility, deformity, unfitness for the throne ... and marriages of desperation.

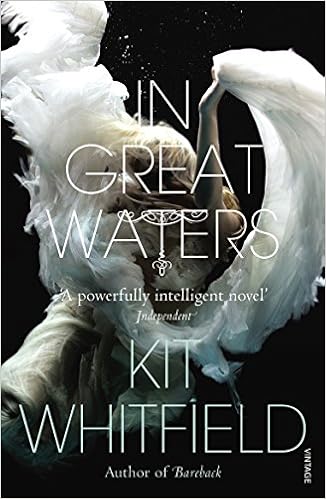

In Great Waters focusses on two young people: Henry, formerly 'Whistle', who's left on the beach by his deepsman mother; and Anne, the younger of two princesses, who has watched her half-deepsman mother negotiate the royal court, and seen that she and her sister Mary are pawns in the game.

Some elements of this novel work better than others. I'm not convinced that the history would be so similar to our own after several centuries of deepsman-landsman interaction. What about colonies, trade by land and sea, anti-deepsman sentiment? And I never really warmed to any of the characters -- though this might be intentional on the author's part, given that the deepsmen are depicted as unsentimental and violent, driven by instinct more than intellect. Henry is certainly an arresting character, but not really a likeable one: when Anne crosses him he looks at her and thinks of eating her tongue.

I found the interpersonal, rather than international, elements of the novel more satisfying. Henry's deep-borne sensorium (he loathes straight lines and corners, thinks the air too thin to carry sound, has poor long-distance vision because he grew up underwater where distance is a 'blue-green blur') is vividly conveyed. Anne's half-crippled state on land -- deepsmen, and those who share their blood, have webbed feet and their legs are 'jointed with vertebrae rather than shin bone and thigh bone' -- contrasts beautifully with her agility and freedom in the sea.

On the whole, though, I didn't enjoy this as much as Whitfield's previous novel, Bareback: strip away the fantasy, and the plot is standard historical fare; strip away the history, and there is an intriguing idea -- a strongly-realised race of merfolk -- that could have been explored more convincingly in a different story, perhaps one set at an earlier stage in the deepsman-landsman entente.

No comments:

Post a Comment