...how Athens came to have the most pure and perfect democracy the world has ever seen, in which every man had a right to be heard, the law was open to all, and nobody need go hungry if he was not too proud to play his part in the oppression of his fellow Greeks and the judicial murder of inconvenient statesmen. [p. 46]

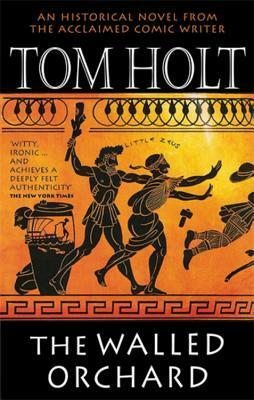

I owned a paperback copy of this novel -- actually two novels in one volume, Goatsong and The Walled Orchard -- for many years but did not read it. Suddenly, recently, the time was right and I was very much in Ancient Greek mode: and I am now much more familiar with the glories of Classical Greece, and the horrors of the Sicilian Expedition, than I was before. (See, for instance, Glorious Exploits.)

The narrator of the duology is Eupolis of Pallene, a gentleman farmer and writer of comedies, from his childhood survival of the plague, which left him scarred and ugly, to his old age. Entwined with the Peloponnesian War and the Sicilian Expedition are the triumphs and disasters of Eupolis' career as a dramatist and his ongoing feud with rival playwright Aristophanes, and his unhappy marriage to Phaedra, a young woman whom he rescues from Aristophanes and his bevy of drunken yobs.

Eupolis loves and hates Phaedra, who is evil-tempered and keen to make her husband look ridiculous: he loves and hates Athens, her shining ideal of democracy and the idiotic voters who perpetuate it. But Aristophanes is the true villain of the piece, even (especially?) when he and Eupolis are fleeing for their lives through hostile Sicily, forced to compose cod-Euripides on the fly to entertain their hosts.

Eupolis' fate is tied to Aristophanes', perhaps by the will of Dionysus. His innate cynicism and stubborn determination -- not to mention his true gift for rhetoric and for comedy -- help him endure the horrors of war, the PTSD afterwards, the sabotage of his final play, and the overthrow of democracy.

I found the Sicilian scenes harrowing and brutal, but extraordinarily vivid because of Eupolis' narrative voice. The minutae of everyday life in classical Greece are recounted with dark humour (though there are also moments of deep joy) and never feel laboured or over-explained. And the greater arcs of the story -- of the decline of Athens, of the horrors of war, of the flaws and failures of democracy -- feel as immediate as today's news.

Democracy is a cannibals’ harvest festival, where everyone does their best to feed the hand that bites them. [p. 519]

No comments:

Post a Comment