And I am thinking of how I am someday going to be writing all this out and I am conscious that I am thinking about this and not about the moment, and I know that I have already escaped the present and that gives me hope, I just have to wait for this to end and I can write again, and I know that because I am going to be writing about this, I know that this is going to end. [loc. 862]

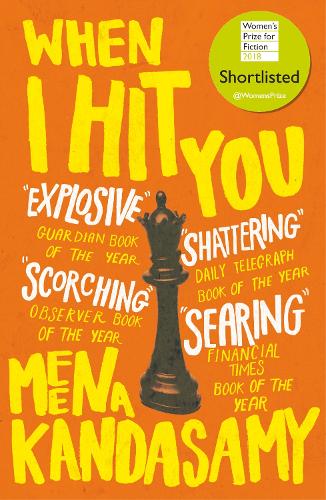

I doubt I'd have read When I Hit You -- a partially autobiographical tale of a physically, mentally and emotionally abusive marriage, told in the first person by a young female writer -- without the Reading Women Challenge 2019, which gave me impetus to buy and read a novel by a woman from 'South Asia' (that is, the Indian subcontinent). And I'm glad I did read it, despite the grim subject matter. Rather than a dystopian vision of The State vs Women -- a theme all too prevalent in fiction and fact, lately -- this is very much a conflict between two individuals. And this narrator survives, walks free, makes her suffering into art, because she tells her own story.

The narrator, never named, is a successful writer who marries a left-wing academic. Unfortunately, it's only after their wedding that she realises he wants to discipline and dominate her. The title of the novel is taken from one of his poems:

When I hit you

Comrade Lenin

weeps [loc. 844]

He forces her to leave Facebook; he curtails her internet use; he deletes all her emails and changes her password; he forbids her to write poetry. He beats her to drive out her demons. ('My demons are not happy. They do not want to leave me to the mercy of this man. They decide to stay.' [loc. 1537]). And because she is afraid of disgracing her family, of seeking a divorce in conservative India, of being blamed, of being hunted down and killed: because of the culture in which she lives, she does not leave. Until she can take control of the narrative: 'his verbal threat ... is enough. It's what I came for. He is scripting the ending that I wanted for us. I generously allow him this authorship.' [loc. 2109].

She (it's hard not to think 'Meena Kandasamy') takes that control, transforming something ugly into something with structure and beauty. This is a writerly escape: that quotation at the top of this review is from the middle of an episode of violence, and the sense of removing oneself from a horrific present is as much an escape for the writer as for the reader. Would it be difficult to revisit times of pain and misery in order to trap them safely in words on a page? Would it be cathartic? Would it be a kind of recycling, repurposing? Would one become numbed by the work of writing it all down?

I don't know. But I think it's important for women -- for all of us -- to tell our own stories.

No comments:

Post a Comment