... the demons winced through their sneers. They rubbed their skins gingerly when they thought they weren’t observed. When they killed and tormented it was in faintly needy fashion. They seemed anxious. They stank not only of sulfur but infection. Sometimes they wept with pain. [p. 28]

This is more novella than novel, but Mieville packs in enough high-culture weirdness, alternate history and arcane travelogue for a much longer book. I'm not sure I'd have had the stamina, though: the prose veers wildly from lyrical and immediate to borderline pretentiousness.

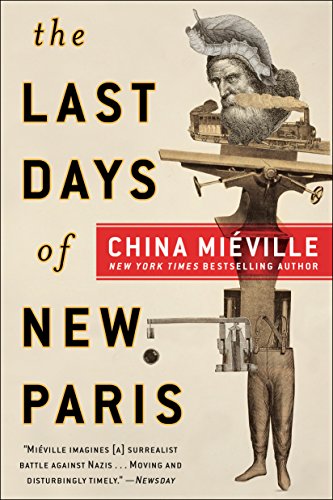

The primary viewpoint character is Thibault, a resistance fighter in a 1950s Paris which is occupied by the Nazis and populated by manifs, Surrealist imagery made concrete: sharks with canoe-seat backs, an Eiffel Tower that's half gone (and not the top half as one might expect), a cycle-centaur, wolf-tables, huge sunflowers and lampposts that shed darkness rather than light. Thibault's comrades are all dead: his blue pyjamas protect him. He encounters a photographer who says her name is Sam, and tells him all about the Nazi attempts to raise demons from Hell to fight the Surrealist manifs. (The demons are miserable.)

Winding around Thibault's and Sam's stories are the adventures of Jack Parsons, an American in Marseilles a decade earlier, who hangs out with Breton and Crowley. Breton is busily reinventing the card deck to reflect troubled times, replacing King-Queen-Jack with Genius-Siren-Magus, the suits with stars, flames, wheels and locks. (This, by the way, is true and I found it fascinating: see this blog post for more about the Jeu de Marseilles.) Parsons, though, thinks he knows how to make a more significant contribution to the war effort.

The Last Days of New Paris has a kind of exuberant joy to its inventiveness. I'm more intrigued by some of the manifs, and by the demons, than by any of the human (or 'human') characters, who felt rather flat. Perhaps at novel length they'd have been fleshed out a little more. Still, as an allegory for the role of art in wartime, and a manifest(ation) of the importance of artistic freedom in a fascist regime, the novella works pretty well.

Reading this on Kindle wasn't ideal: I would have liked illustrations (unable to determine whether there are any in the print version). Here is a useful article of graphic annotations, by Nicky Martin.

No comments:

Post a Comment