She climbed back into her own body — curled up in her heartroom, withdrawing from her sensors and letting go of her bots, space stretching around her, vast and cold and unchanging, the wind whispering against her hull like a lullaby — the sharp light of the stars a restful, familiar sight. [loc. 784]

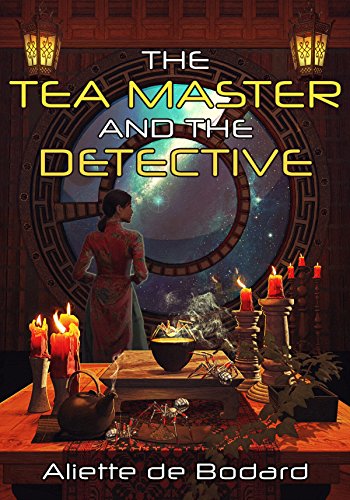

This novella has been described as 'gender-swapped Sherlock Holmes in space', but that pseudoblurb, though accurate, doesn't convey the inventiveness, the depth of character or the ways in which The Tea Master and the Detective subverts and transforms the Holmes/Watson relationship.

The eponymous tea master is The Shadow's Child, a mindship left alone, impoverished and psychologically damaged by war, just about covering the rent by mixing up individual psychoactive blends that let humans deal with the mental and physical distortions of the deep spaces. The detective goes by the name of Long Chau, a human woman whose past The Shadow's Child can't trace. Long Chau wants to buy tea that'll keep her sharp in the deep spaces, the in-between of physical space, where she hopes to find a corpse to study (she's researching the decomposition of the human body in deep spaces). The Shadow's Child needs the money, so agrees -- not expecting to have her secrets, and her past, recounted to her as a series of deductions.

The plot is loosely based on 'A Study in Scarlet', but in a vastly different cultural milieu. Long Chau definitely shares a number of traits with Holmes, but she also has secrets, which pertain to the mystery she's trying -- with the initially reluctant aid of The Shadow's Child -- to solve. Because the corpse she selects, from a wreck in the deep spaces, isn't a casualty of that wreck.

I'm trying to understand why this felt like a story of two halves: as if the author started in one key, and finished in another. It may simply be that as the two protagonists grow more accustomed to one another, they begin to interact more, to communicate more: there's less description of Long Chau's mannerisms, patterns of speech, body language as observed (seen?) by The Shadow's Child.

I only realised after I'd read this that it's set in a universe that de Bodard has explored in other works (notably On a Red Station, Drifting and The Citadel of Drifting Pearls): those works are now on my wishlist, because I'd like very much to explore more of the background. That said, I would love to read more of the interaction between Long Chau and The Shadow's Child.

I also note that The Shadow's Child is the latest in a trope which may have started with McCaffrey's The Ship Who Sang: that was certainly my first encounter with the notion of a living spaceship, a ship that's also a human. Here, there is less ableism, and a sense of family, of parents and relatives, that poor Helga utterly lacked. The Shadow's Child feels like a more rounded -- if less stable -- individual.

No comments:

Post a Comment