She begins to comprehend the mentality of such people. One need not be especially clever, and certainly not well educated. The essential thing is to conduct one’s life as war: everything is permitted except compassion. [loc. 5102]

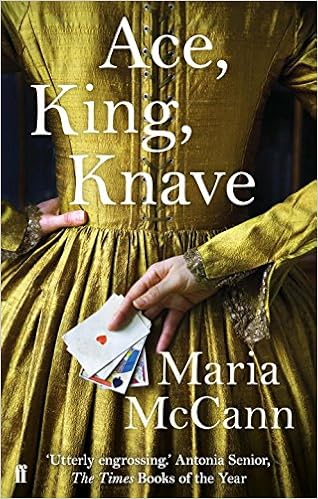

London in the 1760s: or 'Romeville', to the 99% who don't inhabit the clean well-lit civilised world of the gentry. Betsy-Ann Blore is living with a man she despises, having been won by him in a card game with her former lover, the charmingly rakish Ned Hartry. She was once a common prostitute (ensnared by Ned's mother Kitty), but now scrapes a living by thieving and card-sharping. Her brother (the brutish Harry) is a resurrectionist, digging up fresh corpses to sell to anatomists. Betsy-Ann worries that her current fellow, Sam Shiner, will join Harry in his nocturnal adventures.

Sophia Buller, only child of wealthy parents, is newly married to Edmund Zedland, whose business affairs are opaque to Sophia but clearly very lucrative. Why won't he trust her with any of his secrets? And why does his servant, the black boy Titus, seem to hate her? And why do her parents reply so vaguely to her letters?

Sophia's life is lonely, and genteel. Betsy-Ann's quite the opposite, a narrative replete with slang and double-dealing. In Betsy-Ann's world, cruelty is a constant, especially cruelty to -- and by -- women. (The men, in this novel, seem almost peripheral: on the whole they are either well-meaning but ineffectual, or dishonest and violent.)

Sophia and Betsy -- and Titus, whose name is actually Fortunate and who was brought from (or bought in) Annapolis to serve Mr Zedland -- discover how their fates are entwined, and how each of them is the victim of deception. Which leads, in due course, to each of them practicing their own deceptions, with greater or lesser success. This is a novel in which the reader becomes aware of the great central lie before any of the characters realise how they've been duped.

I confess I found Betsy-Ann's narrative richer than Sophia's, but it was also quite breathtakingly unpleasant at times. McCann does an excellent job of comparing and contrasting her two protagonists: her depiction of 'Titus', who can barely speak English but whose interior life is sketched through memory, fancy and despair, is marvellous. And though the novel ends on what, in music, would be called an 'imperfect cadence' (there is no grand resolution) I liked that ending: it works, because it opens up possibilities.

No comments:

Post a Comment