‘Watch out for men who want to turn everything into a story that’s all about them. There will always be a few of them, and once one of them starts, another one of them will want to fight with him.’

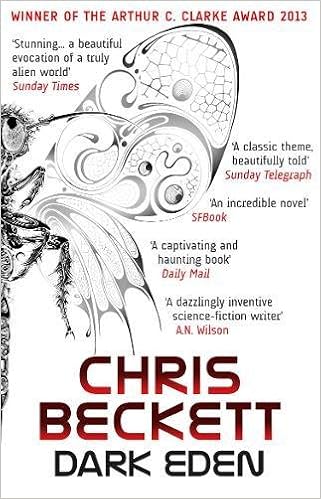

The premise of this award-winning novel -- descendants of stranded spacefarers on a planet with no sun, atavistic society -- did not appeal to me at all, but Dark Eden was recommended by two readers whose opinions I value, so I dived in.

There is a lot to like. The worldbuilding is fascinating: the alien life of Eden, from the trees that are the main source of heat and light to the two-hearted, six-limbed animals with flat eyes that never close, is beautifully and intriguingly described, and the sheer strangeness of this dark world (lit only by harsh starlight when there's no blessed cloud-cover) comes across strongly. The inhabitants are all descended from two individuals, five or six generations before the novel begins: birth defects are common, and few children know who their father is because it hardly matters. Language has simplified (in particular, they seem to have lost the word 'very', so when it's extra-cold it's 'cold cold', or even 'cold cold cold'). The people of Eden, living in a more-or-less matriarchal society, now number over five hundred: and they know that they need to stay near the Circle, where their long-awaited rescuers from Earth will know to find them. Trouble is, local resources are running out. The children no longer have a school, because they can't be spared from foraging. There's talk of a rota system for fishing the lake ...

But one boy, John Redlantern, has radical thoughts. He thinks they should range further, set up other settlements outside the Valley (there must be other valleys which could support life); he listens hard to the old stories and is sure he's noticing elements that nobody's noticed before; he's frustrated with doing things the way they've always been done; he is, in short, a rebel. And he's bored.

In short order John becomes an innovator; an iconoclast; an outcast; a leader of a breakaway community; a criminal of a kind that Eden's never known; and, frankly, the kind of man who makes the story all about him. (Though actually I think that trait's there from the beginning.)

The plot's strongly reminiscent of Lord of the Flies and Clan of the Cave Bear: it's the setting that makes this novel so interesting. There are some significant female characters, too, though many of them are ineffectual or worse. Tina Spiketree, John's girlfriend, is intelligent and observant -- she gets a considerable portion of the narrative -- and she realises that a time is coming when the women will have less power and the men will be running things. One can't help wondering what would have happened if she, rather than John, had had all those bright ideas.

I enjoyed this a great deal more than I'd expected, and found it a truly original setting. I'd like to read more about Eden, but I'm less enthusiastic about the ways in which Eden's society will change after the events of this novel.

Chris Beckett on the science (PDF)

No comments:

Post a Comment