From the height of the window, beyond the canary cages, the immortal Hullocks browsed, burnished and lit, at two in the afternoon. Bowed like silver barrels they were set in rows endwise to the sea. Like pigs, like sheep, like elephants, hay-blond with burnt grass. Velvet's mind stuttered like a small candle before the light and the height and the savage stillness of the middle afternoon. [p. 64]

When I read

National Velvet as a child, I read it as the story of a girl who dreams of horses and whose dreams come true. Reading as an adult, I see a complex and layered story about mothers and daughters, different kinds of love, and the purity of Velvet's dream.

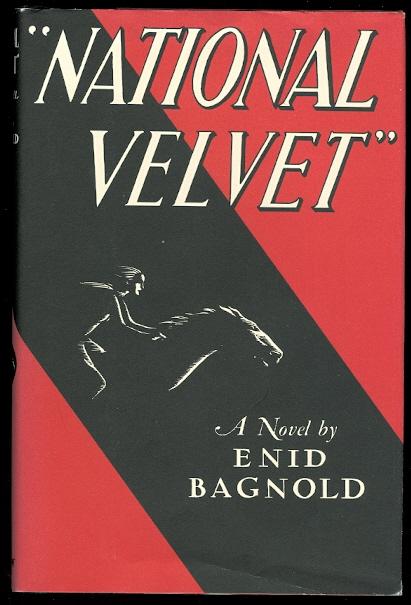

Initially published in 1935 -- as a novel for adults, not the children's book it was later marketed as --

National Velvet is the story of a butcher's daughter who wins a horse in the village raffle, and inherits another five from a local eccentric. She and her sisters (who are nothing like her) compete in the local gymkhana: then Velvet, in collusion with her father's assistant Mi Taylor (a young man with a mysterious past), enters the Grand National on her raffle-prize horse, disguised as a boy: and wins.

Except that there's so much more to the story. The way the actual National is described -- in glimpses through the crowd as Mi shoves and rushes towards the finish line, never sure if Velvet's still in the race -- is enough to tell us that. (I'm glad it doesn't describe the National in much detail: that race's massive equine death toll is horrific.)

National Velvet is also a story about Velvet's mother Araminty, who swam the Channel as a young woman coached by Mi's dad, and who sees something of her own spirit in her youngest daughter. It's also Mi's story,a swim coach's son who can't swim and hates water, who knows horses but doesn't ride. And the story of the five children of Mr Brown the Butcher, the three golden sisters and their baby brother with the film-star looks, and Velvet who is plain and has bad teeth, growing up in poverty in rural Sussex between the wars, getting Mars bars and Crunchies on tick at the local shop, accepting that there's the ghost of a horse at a difficult corner, dreaming of horses.

(When is this novel set? It has to be, Bagnold tells us, before 1931, when the rules of the National were changed to prohibit horses without a history of steeplechase wins; but it has to be after 1930, because Velvet is described as being victim to a 'Lindbergh-Amy Johnson' sort of press frenzy, but Amy Johnson only hit the headlines with her solo flight to Australia in May 1930 ... The Past, we can safely say: the England in which my mother, a baker's daughter born in the mid-1920s, grew up.)

As always when I reread, I was surprised by what I remembered (one of the sisters getting splatted by birdshit, Araminty's corsetry, the phrase 'hands like piano wires') and what I'd forgotten or never noticed (Araminty's brief flash of panic when Velvet confides 'me and Mi are in this together', before she realises that her daughter is 'not all messed up with love an' such', but only with the love of a horse; the Russian jockey whose horse dies at Croydon airport; the fact that the Piebald was neutered late, and not terribly well, and thus is thick-necked and wilful).

There is some glorious writing here too. I'd never seen the Sussex Downs when I first read the book, and had no visual reference: but the vast loom and the empty golden hilltops resonate now, and perhaps resonated in my subconscious when I did visit that landscape.

And there are so many different kinds of love here: the wordless sexless love of Mi for Velvet and his father for her mother ('there are men who like to make something out of women'), the dog that the family loves 'as they loved each other, deeply, from the back of the soul, with intolerance in daily life', the quiet enduring love between Araminty and her rather colourless husband, the youthful passion of Edwina and her beau Teddy, Malvolia's love for her canaries: and Velvet's love for horses, and above all for the Piebald. "If you could see what he did for me ... I'd sooner have that horse happy than go to heaven," she says.

This is a book that focuses on the female characters, but doesn't gloss over the sexism of the period. Velvet couldn't have pulled off the ruse without Mi's help: she has no access to the racing circles in which he moves, and would never have been taken seriously without Mi's preparatory work. A generation earlier, Araminty's Channel swim was possible only because of Dan Taylor's coaching: and when she came to land at Calais, the press descended and (implicitly) treated her as a spectacle. Mr Brown hopes his girls will marry well: he forces Velvet to wear a painful brace so that her teeth will be respectable. The women are wasted, in a sense. Of Araminty, early on: 'it would have taken a war on her home soil, the birth of a colony, or a great cataclysm to have dug from her what she was born for'. She's glad of her daughters, for she doesn't understand the courage of men. ... Interesting to put this in context: Mr and Mrs Brown lived through the First World War, and likely thought it could never happen again. Perhaps Donald, the baby of the family, is young enough that he won't serve in the Second World War. Perhaps.

Read, via the

Internet Library -- unaccountably there is no ebook edition! -- for the 'woman athlete' rubric of the

Reading Women Challenge 2019 on Goodreads.